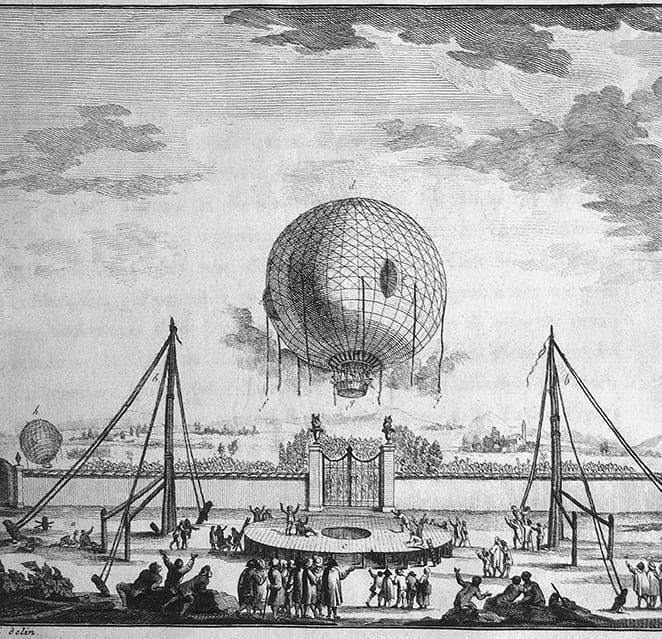

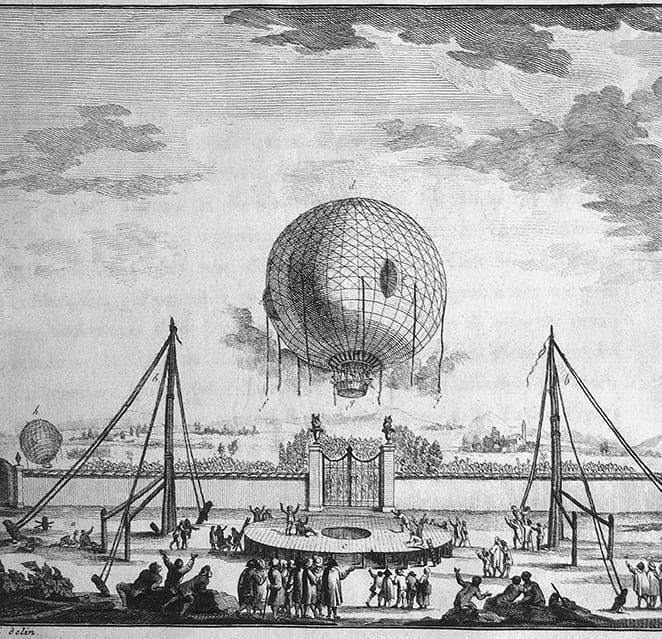

Already at the time of the very first experiments, intrepid airmen were studying the way to somehow direct their "flying ships". It is really incredible the variety of instruments that at the time were used in the attempt: rotating blades, propellers, sails, rudders, even cannons that would generate an action-reaction effect allowing the advance of the balloon in the desired direction, or even the use of large raptors trained to "pull" balloons.

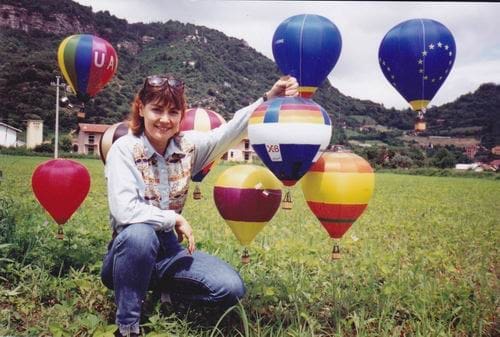

dav

Mauro Argiolas

castle

castle

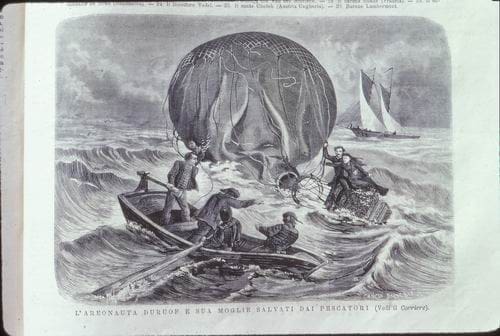

Monsieur and Madame Garnerin

Monsieur and Madame Garnerin

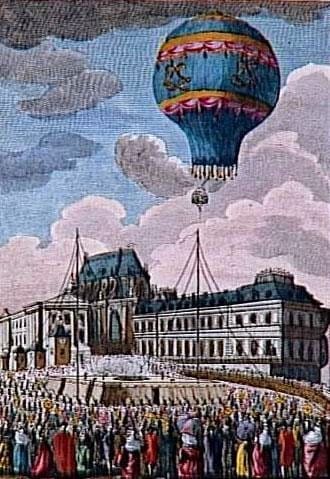

George Biggins ascent in Lunardi’s balloon

*oil on canvas

*50.5 x 61 cm

*ca 1785-1788

George Biggins ascent in Lunardi’s balloon

*oil on canvas

*50.5 x 61 cm

*ca 1785-1788

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Francesco Arban

Francesco Arban di Lione. Head-and-shoulders portrait of French balloonist Francesco Arban di Lione commemorating his twelfth flight. Date 1846.

Today we know that all these attempts were destined to fail because it is not possible, by applying any propulsive force to an object of spherical shape or almost, to give it a directional thrust. The possible thrust would only serve to make the balloon rotate on itself. By the same principle a boat pulled by the current of a river, can not be in any way direct, whatever position took the helm. Vincenzo Lunardi, in far 1785, during one of his flights to the land of Scotland, he showed that he had understood the general principles of flying in a balloon, so much so that, taken off from Edinburgh, He landed in the garden of his friend Baron Dick Bocan’s villa, who had invited him to lunch. After he had rested, he took up the balloon and, hanging a long rope on it, was hauled back to Edinburgh, where he descended into George Square, the square in which other friends of his, including the knight Pringle, dwelt, tying the ball’s rope to the railing and "Leaving it there until one in the morning". The same principles that guided the aeronauta of Lucca in the eighteenth century are still at the base of modern hot air balloons.

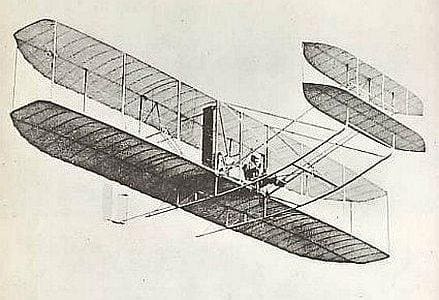

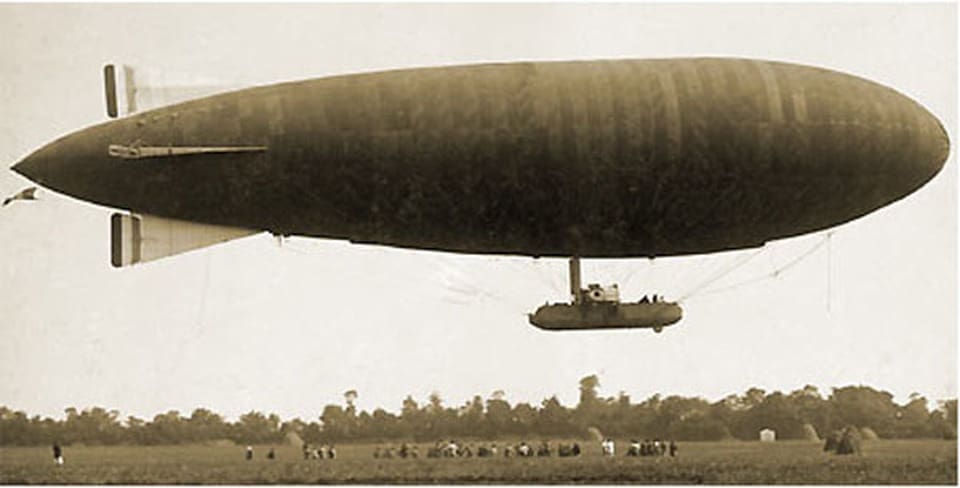

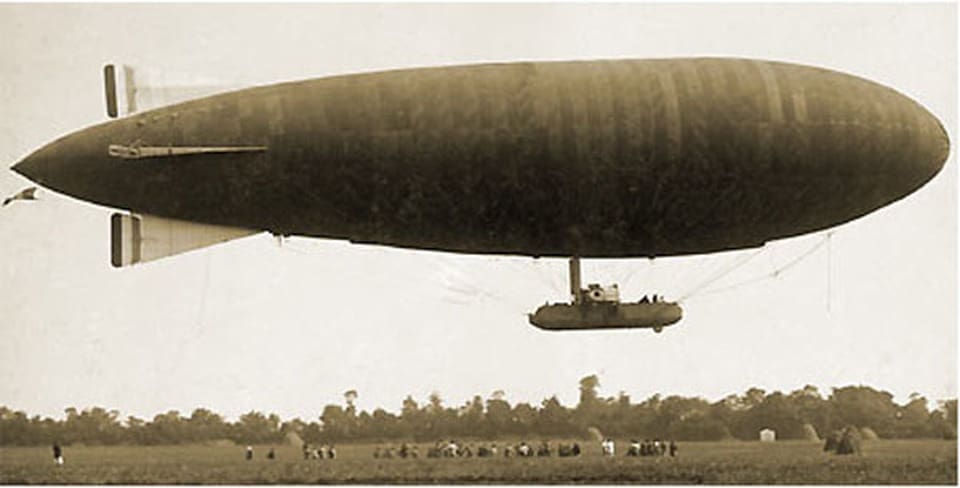

It would be many decades before the aeronautics realized that to ensure the steerability it would be necessary to change the shape of the balloon, making it more and more oblong, and to apply to it a sufficiently powerful, but also light enough, propellant, It ensures a good weight/power ratio.

The evolution of engines, more and more powerful and lighter, finally led to the manufacture of the first real airship. It was in 1884 in Paris, when for the first time, also following the intuitions of the Venetian engineer Pasquale Cordenons, Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs managed to make a closed circuit to their own aerial machine, He proved that he could also travel against the wind, using an electric motor. Cordenons had actually designed a dirigible with an engine that would allow the pilot to "go in search of periodic regional cyclic atmospheric currents", so he had sensed the basic principle of aerostatics. In summary, Cordenons had deduced that the contemporary engines would not have the necessary power to oppose the wind and that each air flow must have its own opposite of equal intensity at a different altitude, to allow the continuous equilibrium of the atmosphere: a concept which is generally correct in the first approximation.

After the successful conclusion of the airship experiments La France Renard and Krebs, the development of this type of aircraft went hand in hand with the creation of engines that were increasingly powerful and efficient, allowing the production of large aircraft which had been flying since the early years of the twentieth century. The pioneer was certainly the rich Brazilian entrepreneur Alberto Santos-Dumont, who still in Paris in 1899 developed a single-seat airship, a kind of flying car, named La Baladeuse, grazie al quale si vantava di andare a trovare gli amici che abitavano fuori-porta e perfino di recarsi al suo bar preferito!

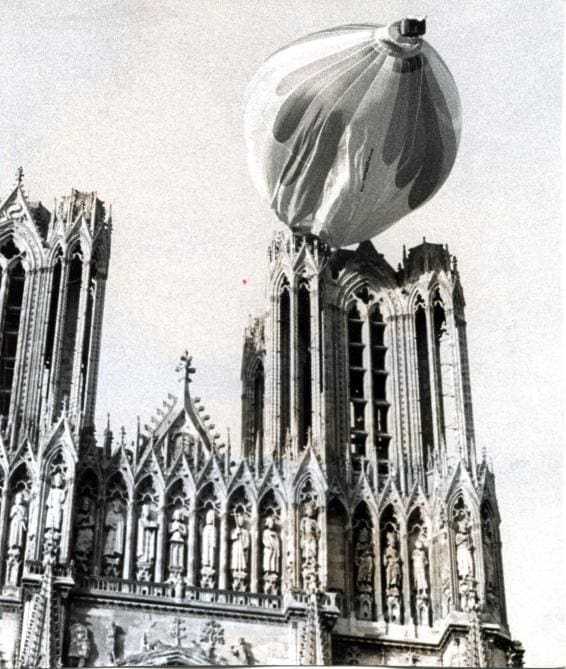

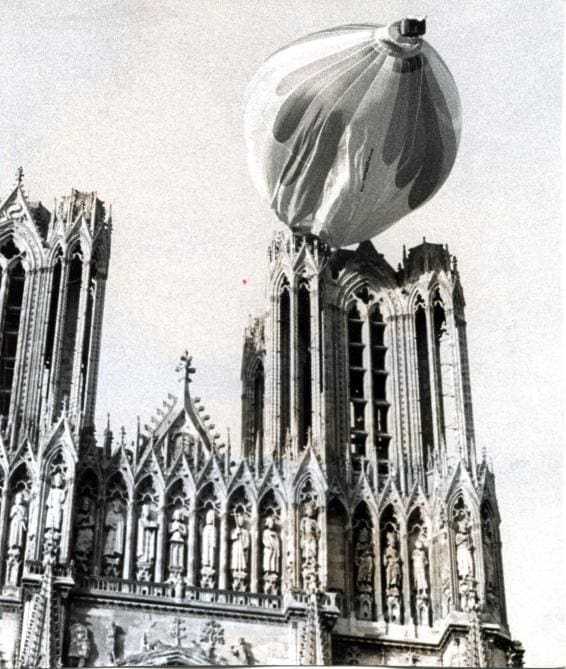

From 1910, while the airplane, a much more fearsome rival, was increasingly establishing itself in the mode of flight, airships experienced a period of great technological and dimensional development, also establishing themselves as a military instrument. The Italians in the Libyan War in 1911 were the first to use these aircraft to carry out the first air bombardments in history. A record that we would have liked to do without!

The airships could fly even at 3000 meters and were therefore practically invulnerable since the first airplanes could not rise above a few tens or hundreds of meters and the ranges of guns and machine guns were not enough to shoot down the formidable and Rather quiet flying ships. As often happens, the First World War was a great driving force for the technological development of aviation and in 1917 aircraft began to reach the airships' quota, limiting their military effectiveness.

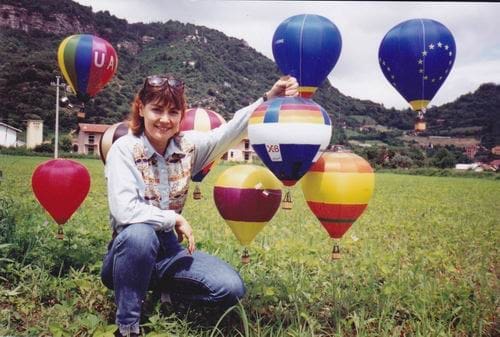

The left postcard was created on the occasion of the 33rd Mondovi Hot Air Balloon Rally by Giovanni Gastaldi, a young Monregalese illustrator!

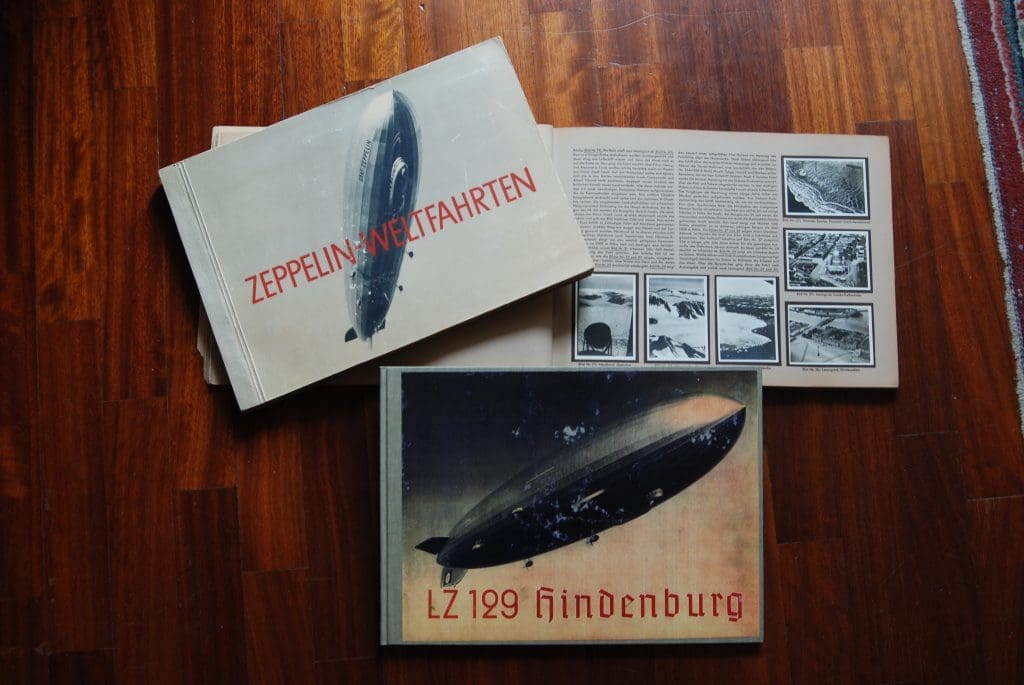

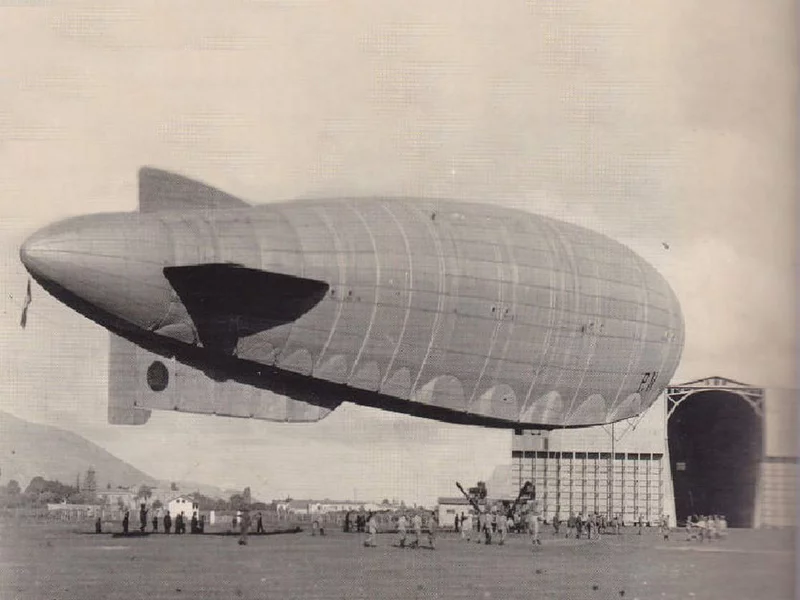

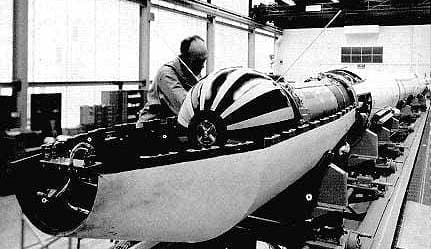

After the war, airship manufacturers, especially the German Zeppelin, built machines capable of carrying up to 80-90 passengers across the oceans. The German enterprise of 1929 Graf Zeppelin LZ 127 who for the first time made a complete round-the-world trip. In the years from 1925 to 1937, we witnessed the manufacture of the largest and fastest airships, culminating with theHindenburg, 247 meters long and 203,000 cubic meters in volume, the largest flying machine ever built by man. Aboard one of these airships you lived in total luxury: fine wines and starred chefs prepared sumptuous lunches and dinners on board during the four days of the Atlantic crossing. The price of the ticket was comparable to 6-7000 euros today. Even many brilliant Italian builders realized aircraft such as the T34 – Roma of Celestino Usuelli, then sold to the US Navy or the innovative articulated airships of Gaetano Arturo Crocco.

The polar exploits of Umberto Nobile and Roald Amundsen in 1926 (airship Norge) and in 1928 (airship Italy) allowed man to reach the North Pole for the first time.

But by the end of the 1930s, the age of transatlantic airships was coming to an end. The planes were increasingly conquering the atmosphere world and the disaster ofHindenburg, which caught fire in unknown circumstances in 1937 during the docking phases on arrival in the United States, marked the end of the airships.

The outbreak of World War II marked the final sunset for these ships of the sky, which became slow and vulnerable, as well as immensely expensive.

Today we continue to talk about "rebirth" of the airship, as a means capable of transporting extremely heavy and bulky loads even in the center of the continents, in areas almost uninhabited and not located near ports or served by roads sufficiently wide, The technical limits are insurmountable and the costs are too high, although many companies continue to develop interesting projects. The costs of inflating with a lighter gas than air are also constantly rising, especially if you want to use inert helium instead of the flammable and explosive hydrogen with which the first airships were inflated. Helium, which was isolated in quantity only around 1910, is now becoming increasingly expensive as a rare by-product of oil fields.

The current use of airships seems increasingly aimed at surveillance tasks due to the fact that these vehicles are able to stand for a long time at high altitudes without consuming fuel and proving to be ideal platforms for television or photographic. The glorious Zeppelin still exists and produces aircraft capable of carrying a dozen passengers over tourist areas, but the costs are always very high. We believe that the historical chapter of airships is destined to have no major developments in the near future, even in the light of the recent and overbearing assertion of a very modern flying vehicle much more practical and manoeuvrable, the drone.